The Chimu City of Chan Chan

The coastal desert of northern Peru conceals an urban mystery that’s puzzled archaeologists for decades. Chan Chan, once the Americas’ largest adobe metropolis, housed 60,000 people before vanishing into history. Its nine forbidden citadels and maze-like corridors suggest something more complex than simple abandonment. The city’s sudden rise from the Moche civilization’s ashes and its equally dramatic fall hint at forces that weren’t entirely natural.

Introduction

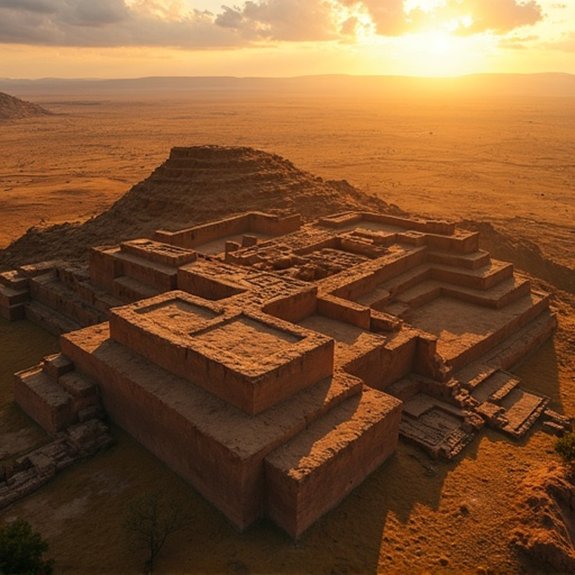

When the Spanish conquistadors first encountered Chan Chan in the 16th century, they’d stumbled upon the largest adobe city ever built in the Americas. This vast urban center served as the capital of the Chimú Empire from approximately 900 to 1470 CE, covering twenty square kilometers along Peru’s northern coast near modern-day Trujillo.

At its height, Chan Chan housed between 40,000 and 60,000 inhabitants. The city’s sophisticated design included nine walled citadels, each containing royal palaces, ceremonial plazas, and storage facilities. Chimú architects constructed the entire complex from sun-dried mud bricks, creating intricate geometric friezes and carved reliefs that decorated palace walls. The city’s elaborate irrigation system channeled water from the Moche River, supporting gardens and reflecting pools throughout the urban landscape.

Moche Collapse Enabled Chimu Rise

Although the Moche civilization had dominated Peru’s northern coast for centuries, its sudden collapse around 750 CE created a power vacuum that the Chimú would eventually fill. Climate disruption, including severe droughts and catastrophic flooding from El Niño events, devastated Moche agricultural systems and triggered widespread social upheaval. The Moche’s centralized authority crumbled as their ceremonial centers fell into disuse and populations dispersed.

For nearly two centuries, smaller polities competed for regional control. The Wari and Lambayeque cultures briefly held influence, but neither achieved lasting dominance. Around 900 CE, the Chimú emerged from the Moche Valley, inheriting advanced irrigation techniques and metalworking traditions from their predecessors. They’d learned from the Moche’s vulnerabilities, developing more resilient agricultural strategies and flexible administrative systems that enabled rapid territorial expansion.

Notable Cases or Sightings

Since early Spanish chronicles first documented Chan Chan in the 16th century, the city’s massive scale has astounded visitors and researchers alike. Francisco Pizarro‘s conquistadors reported finding vast adobe walls stretching across the coastal plain, though they’d already been abandoned for decades. In 1969, Michael Moseley’s archaeological team uncovered the Rivero compound‘s intricate friezes depicting fish, pelicans, and mythological beings. The 1997 El Niño rains exposed previously hidden polychrome murals in the Uhle complex, revealing the Chimu’s sophisticated artistic techniques.

Today’s visitors can’t miss the iconic net-like patterns carved into the Tschudi Palace walls. Satellite imagery from 2018 identified seventeen previously undocumented structures beneath sand dunes. Local fishermen still report seeing Chan Chan’s eroded pyramids emerge during extreme low tides, evidence of the ancient capital’s enormous footprint.

Common Theories or Explanations

While archaeologists have proposed numerous theories about Chan Chan’s rise and fall, most explanations center on the Chimu’s masterful control of water resources in Peru’s arid coastal desert. They’ve identified sophisticated irrigation systems that channeled rivers through extensive canal networks, enabling agricultural surplus that supported urban growth. The city’s planned layout suggests centralized authority coordinated massive construction projects requiring thousands of workers.

Climate change theories dominate discussions about Chan Chan’s abandonment. Evidence points to severe El Niño events and prolonged droughts that disrupted water supplies. Some researchers argue the Inca conquest in 1470 wasn’t purely military—they systematically dismantled Chimu water infrastructure to force submission. Others propose epidemic diseases weakened the population before Spanish arrival accelerated the city’s final decline.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Much Does It Cost to Visit Chan Chan Today?

Visitors pay approximately 10-11 Peruvian soles (about $3 USD) to enter Chan Chan’s main archaeological complex. The ticket also includes access to the site museum and Huaca Esmeralda. Prices haven’t changed noticeably since 2023.

What Are the Opening Hours for Tourists Visiting the Site?

Chan Chan’s archaeological site opens daily from 9:00 AM to 4:00 PM for tourists. Visitors should arrive early since the site’s vast and exploring takes several hours. The ticket office closes at 3:00 PM.

How Do I Get to Chan Chan From Nearby Cities?

Visitors can reach Chan Chan from Trujillo’s city center by taking a 20-minute taxi ride or local bus. They’ll find the archaeological site located 5 kilometers northwest of Trujillo along the Pacific coast highway.

Are Guided Tours Available in Different Languages?

Yes, Chan Chan offers guided tours in multiple languages including Spanish, English, French, and German. Visitors can book these through local tour operators in Trujillo or arrange them directly at the site’s entrance.

What Facilities and Amenities Exist for Visitors at the Site?

Chan Chan’s visitor facilities include a site museum, restrooms, parking areas, and a ticket office at the entrance. There’s limited shade, so visitors should bring sun protection. Basic souvenir shops operate near the main complex.