The Lost Civilization in the Sahara

The Sahara’s ancient Garamantian Empire shouldn’t have existed where it did. Between 1000 BCE and 700 CE, this sophisticated civilization built fortified cities and engineered complex irrigation systems across what’s now barren wasteland. Greek explorers documented their encounters with these desert dwellers, yet historians dismissed their accounts as fantasy for centuries. Recent archaeological discoveries have vindicated those ancient testimonies, but they’ve also raised disturbing questions about what really happened to the Garamantians.

Introduction

When ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote about a thriving civilization deep within the Sahara Desert, most scholars dismissed his accounts as fantasy. They couldn’t imagine advanced societies existing in what’s now the world’s largest hot desert. However, recent archaeological discoveries have vindicated Herodotus’s claims, revealing evidence of the Garamantian Empire that flourished between 1000 BCE and 700 CE.

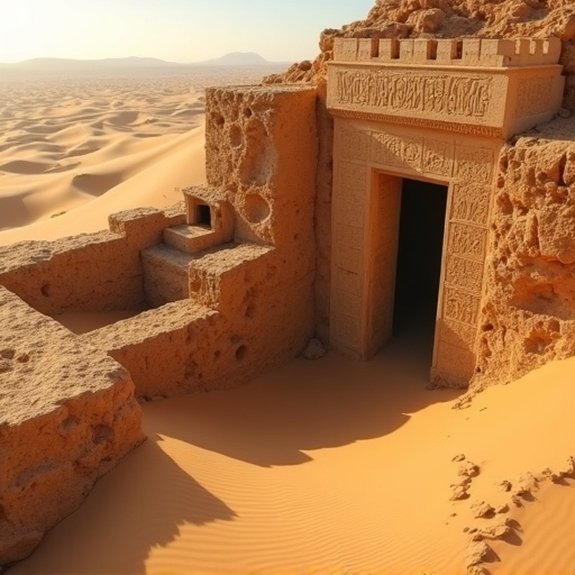

Satellite imagery has exposed vast irrigation systems, fortified cities, and trade networks buried beneath sand dunes. These findings prove the Sahara wasn’t always barren. Climate data shows the region experienced periodic “green” phases when monsoons transformed it into fertile grasslands. During these periods, sophisticated civilizations developed agriculture, built monuments, and established trans-Saharan trade routes that connected sub-Saharan Africa with the Mediterranean world.

Ancient Greek Explorer Accounts

Greek explorers documented remarkable encounters with Saharan peoples that modern archaeology has only recently confirmed. Herodotus wrote about the Garamantes, describing their underground irrigation systems and four-horse chariots that crossed vast desert expanses. He’d collected these accounts from traders who’d ventured deep into Libya’s interior regions.

Later explorers like Marinus of Tyre mapped trade routes extending beyond the Atlas Mountains, noting prosperous settlements where archaeologists now find ruins. They’ve discovered that Greek descriptions weren’t exaggerations—these civilizations possessed sophisticated water management and extensive trading networks reaching sub-Saharan Africa.

The Greeks called the region “Libya Interior” and recorded its inhabitants’ unique customs, including their matrilineal societies and distinctive burial practices. These accounts provide vital evidence that the Sahara wasn’t always the barrier it’s become today.

Notable Cases or Sightings

How did twentieth-century explorers stumble upon evidence of lost Saharan civilizations that had vanished millennia ago? In 1933, Hungarian explorer László Almásy discovered prehistoric cave paintings in Egypt’s Gilf Kebir plateau, depicting swimmers in what’s now barren desert. French archaeologist Henri Lhote documented 15,000 rock art images at Tassili n’Ajjer in Algeria during the 1950s, showing lush scenes with giraffes, elephants, and cattle herders.

Satellite imagery revolutionized discoveries. In 2011, archaeologists using Google Earth identified hundreds of fortified settlements along ancient Libyan trade routes. David Mattingly’s team found the Garamantian kingdom’s extensive irrigation system buried beneath sand dunes. Most recently, radar technology revealed a vast river network under Mauritania’s Eye of the Sahara structure, suggesting it once supported major populations before desertification.

Common Theories or Explanations

These remarkable discoveries have sparked competing theories about what caused thriving Saharan societies to disappear. Climate scientists point to dramatic environmental shifts around 5,000 years ago, when monsoon patterns changed and transformed the region from grassland to desert. They’ve found evidence of rapid desertification in sediment cores and ancient lake beds.

Archaeologists propose that overgrazing and poor land management accelerated the natural drying cycle. Some researchers believe volcanic eruptions or asteroid impacts triggered sudden climate change. Others suggest disease outbreaks or warfare between competing groups led to societal collapse.

Migration theories have gained traction recently. Evidence shows populations didn’t simply vanish but relocated to the Nile Valley and sub-Saharan regions. Genetic studies support this, revealing DNA links between modern North African populations and ancient Saharan peoples.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Modern Technologies Are Being Used to Search for Ruins Beneath the Sand?

Archaeologists’re using satellite imagery, ground-penetrating radar, and LiDAR technology to detect buried structures beneath the Sahara’s sand. They’re also employing drones equipped with thermal cameras and magnetometers to identify ancient settlements and artifacts.

How Can Tourists Safely Visit Potential Archaeological Sites in the Sahara Region?

Tourists can’t safely visit potential archaeological sites without licensed guides who’ll provide proper equipment, water supplies, and navigation tools. They must obtain permits, travel in groups, avoid extreme temperatures, and respect restricted excavation areas.

What Permits or Permissions Are Needed to Conduct Archaeological Excavations There?

Archaeologists need government permits from the host country’s antiquities department, they’ll obtain research visas, secure local community consent, and acquire environmental clearances. They’re also required to partner with national institutions and follow UNESCO guidelines.

Which Museums Currently Display Artifacts Potentially Linked to This Lost Civilization?

Several museums don’t specifically display artifacts from a confirmed “lost Sahara civilization” since it’s hypothetical. However, Cairo’s Egyptian Museum, Paris’s Louvre, and London’s British Museum showcase ancient Saharan artifacts that researchers sometimes link to unknown cultures.

What Funding Opportunities Exist for Researchers Studying Saharan Prehistoric Civilizations?

Researchers can apply for grants from UNESCO’s World Heritage Fund, National Geographic Society’s exploration grants, and the European Research Council’s funding programs. They’ll also find opportunities through the Leakey Foundation and various national archaeological institutes.