The Mystery of Gobeki’s Animal Reliefs

The stone pillars of Göbekli Tepe hold secrets that’ve puzzled archaeologists since their discovery. Carved with predators, birds, and serpents, these 11,000-year-old reliefs predate agriculture and challenge everything scholars thought they knew about early human civilization. Why did hunter-gatherers invest such effort in creating these elaborate symbols? The answer might reshape our understanding of humanity’s first steps toward organized society, but the true meaning remains locked in stone.

Introduction

When archaeologists first uncovered Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey during the 1990s, they couldn’t believe what they’d found—a massive temple complex that predated Stonehenge by over 6,000 years. The site’s T-shaped limestone pillars, some reaching 20 feet tall and weighing up to 10 tons, challenged everything experts thought they knew about prehistoric societies.

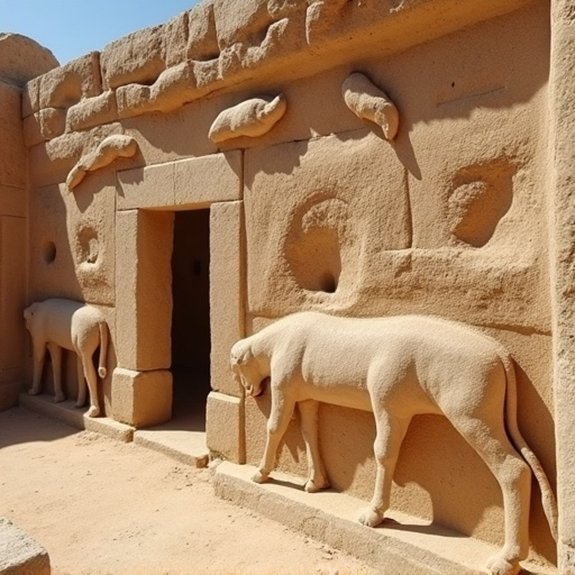

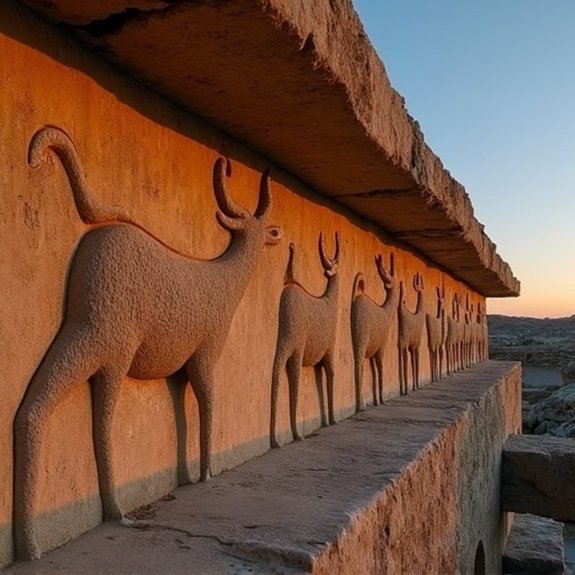

What’s captivated researchers most are the intricate animal reliefs carved into these ancient megaliths. Snakes, foxes, lions, birds, and scorpions dance across the stone surfaces in remarkable detail. These weren’t simple scratches—they’re sophisticated artworks created by hunter-gatherers who supposedly lacked the tools and social organization for such monumental construction. The carvings raise fundamental questions about early human symbolism, religious practices, and the capabilities of pre-agricultural societies 11,500 years ago.

Discovery in 1963 Turkey

Although German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt typically gets credit for Göbekli Tepe‘s discovery, a survey team actually first noted the site in 1963. The University of Chicago and Istanbul University’s joint expedition surveyed southeastern Turkey’s prehistoric sites that year. They cataloged the limestone slabs protruding from a hill’s surface but didn’t recognize their significance. The team mistakenly identified them as Byzantine cemetery markers.

The site remained unexplored for decades. Local farmers called the hill “Potbelly Hill” due to its rounded shape. They’d occasionally plow up carved stones, moving them to field edges. Schmidt revisited the 1963 survey reports in 1994. He immediately recognized the site’s potential importance from the descriptions. His subsequent excavations revealed humanity’s oldest known temple complex, predating Stonehenge by 6,000 years.

Notable Cases or Sightings

Since Schmidt’s excavations began in 1995, archaeologists have uncovered remarkable animal reliefs that’ve puzzled researchers worldwide. Pillar 43, dubbed the “Vulture Stone,” displays a headless human figure surrounded by vultures and scorpions. This particular carving has sparked intense debate about possible astronomical alignments or death rituals.

The site’s most striking discovery came in 2003 when teams revealed the lion pillar complex. These limestone columns feature snarling felines with exposed teeth, standing over three meters tall. Enclosure D contains twin pillars depicting foxes, boars, and serpents in extraordinary detail.

In 2014, researchers documented previously hidden reliefs using 3D scanning technology. They’ve identified over sixty different animal species carved throughout the site, including cranes, ducks, and wild cattle that hadn’t existed in the region for millennia.

Common Theories or Explanations

Archaeological interpretations of Göbekli Tepe‘s animal reliefs have generated three dominant theories among researchers. The astronomical hypothesis suggests the carvings represent constellations and celestial events, with pillars functioning as an ancient star map. Proponents argue the site’s orientation and specific animal arrangements correspond to prehistoric sky patterns.

The shamanic theory proposes these reliefs depict spirit animals encountered during ritual trances. Researchers cite the prominence of predators and birds—common shamanic symbols—as evidence for transformative ceremonies.

The territorial marking explanation views the animals as clan totems or regional identifiers. Different groups may’ve carved their symbolic animals to establish sacred boundaries or commemorate gatherings. Each pillar’s unique combination could represent alliances between tribes.

These theories aren’t mutually exclusive; the site’s complexity likely encompasses multiple symbolic layers.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Tourists Visit Göbekli Tepe to See the Animal Reliefs in Person?

Yes, tourists can visit Göbekli Tepe to see the ancient animal reliefs. They’ll find the archaeological site open to visitors with walkways and viewing platforms that provide access to the excavated stone pillars and carvings.

What Tools and Techniques Were Used to Carve These Intricate Animal Reliefs?

Ancient craftsmen carved Göbekli Tepe’s animal reliefs using flint and obsidian tools. They’d employed pecking, grinding, and polishing techniques on the limestone pillars, creating detailed representations through patient stone-on-stone work without metal implements.

How Much Does It Cost to Fund Excavation Work at the Site?

Archaeological teams spend approximately $500,000 to $1 million annually excavating Göbekli Tepe. Turkey’s government provides primary funding, while international universities and research grants contribute additional support. Private donors occasionally sponsor specific excavation seasons or conservation projects.

Are There Similar Animal Relief Sites Found Elsewhere in the World?

Yes, archaeologists have discovered similar animal reliefs at sites like Çatalhöyük in Turkey, Lascaux Cave in France, and Indonesia’s cave art. These sites share Göbekli Tepe’s focus on depicting wild animals through carved or painted imagery.

What Preservation Methods Protect the Reliefs From Weathering and Damage?

Archaeologists protect Göbekli Tepe’s reliefs through protective shelters, controlled visitor access, and environmental monitoring. They’ve installed roofing structures, apply consolidation treatments to fragile stone, and use barriers that prevent direct touching while maintaining site integrity.