The Mystery of Petra’s Hidden Chambers

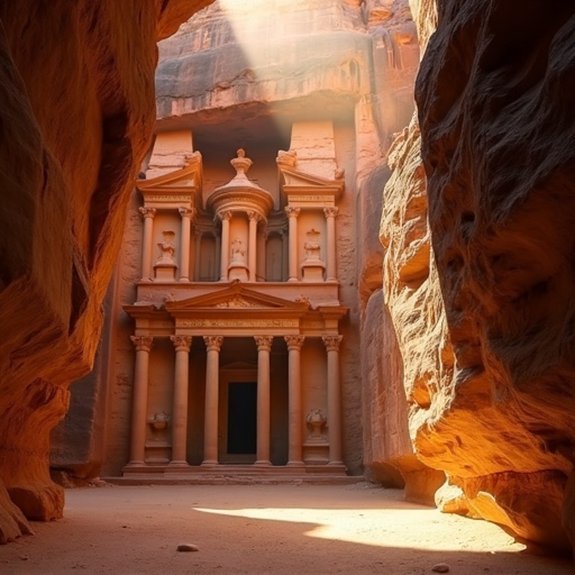

Petra’s sandstone cliffs aren’t telling the whole story. Ground-penetrating radar‘s detected massive voids beneath the ancient Nabataean city, spaces that shouldn’t exist according to conventional archaeology. While tourists marvel at the Treasury’s facade, scientists map subterranean chambers that’ve remained sealed for two millennia. The technology’s revealing an underground network far more extensive than anyone imagined. What the Nabataeans built down there—and why they hid it—remains frustratingly out of reach.

Introduction

What drives archaeologists to spend decades excavating the ancient city of Petra, convinced that its greatest secrets still lie buried beneath millennia of sand and stone? They’re drawn by tantalizing evidence of undiscovered chambers within the rose-red cliffs of Jordan’s most famous archaeological site. Recent ground-penetrating radar surveys have revealed massive voids beneath the Treasury and other iconic structures, suggesting that Petra’s visible monuments represent only a fraction of what the Nabataeans created two thousand years ago.

These findings have reignited scientific interest in the site. Teams now deploy advanced imaging technology to map subterranean spaces without damaging the delicate sandstone. Each discovery raises new questions about the civilization that carved an entire city from living rock and controlled crucial trade routes between Arabia, Egypt, and the Mediterranean world.

Nabataean Engineering Mastery

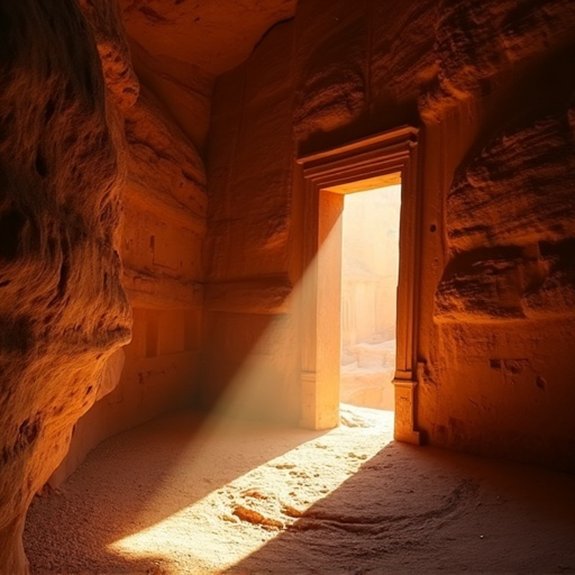

Ingenuity defined the Nabataean approach to carving Petra from solid rock faces. They didn’t merely chisel facades; they engineered complex water management systems that defied desert conditions. Channels carved into cliffsides directed rainwater into cisterns, while settling tanks filtered sediment before storage.

The Treasury’s facade demonstrates their precision—its columns, pediments, and sculptures weren’t added but subtracted from sandstone. Workers carved from top to bottom, eliminating scaffolding needs. They calculated stress points, ensuring structural integrity despite removing tons of rock.

Their understanding of geology proved remarkable. They selected sandstone layers resistant to erosion and positioned monuments where natural rock formations provided protection from flash floods. This technical mastery allowed them to create chambers extending deep into mountains, spaces that still puzzle archaeologists today.

Notable Cases or Sightings

These engineering achievements make recent discoveries all the more intriguing. In 2016, archaeologists used ground-penetrating radar to detect a massive platform beneath Petra’s Treasury, suggesting unexplored chambers below. They’ve identified anomalies indicating hollow spaces behind several tomb facades that remain sealed.

Local Bedouins have reported strange acoustic phenomena near the Monastery, where certain walls produce echo patterns inconsistent with solid rock. In 2018, a research team documented temperature variations along the Siq’s walls that don’t match the surrounding geology, hinting at concealed passages.

Most significantly, satellite thermal imaging has revealed heat signatures beneath the Royal Tombs complex that shouldn’t exist in solid sandstone. These findings suggest Petra’s architects created far more elaborate underground networks than previously thought, with potentially dozens of chambers still hidden.

Common Theories or Explanations

While archaeologists debate the purpose of Petra’s hidden chambers, several compelling theories have emerged to explain their existence. Many experts believe they’re unfinished tombs, abandoned when builders encountered unstable rock formations or funding dried up. Others suggest they served as storage facilities for precious goods, religious artifacts, or water during sieges.

Some researchers propose these spaces functioned as meditation chambers for Nabataean priests, pointing to acoustic properties that enhance chanting. A controversial theory claims they’re part of an elaborate drainage system, channeling flash floods away from main structures. Recent geological surveys indicate certain chambers might’ve been naturally occurring caves that ancient inhabitants modified. Each theory reflects different aspects of Nabataean culture—their engineering prowess, religious practices, and practical adaptations to desert life.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Tourists Visit the Hidden Chambers if They Are Discovered?

Tourists can’t automatically visit newly discovered chambers in Petra. Jordan’s authorities would first assess safety, structural integrity, and preservation needs. They’d likely restrict initial access to archaeologists and researchers before considering regulated public viewing options.

What Permits Are Required for Archaeological Excavation at Petra?

Archaeological teams need Jordan’s Department of Antiquities permits before excavating at Petra. They’ll submit detailed research proposals, demonstrate professional qualifications, and obtain UNESCO approval since it’s a World Heritage Site requiring strict preservation protocols.

How Much Would a Full Excavation of Hidden Chambers Cost?

Experts estimate a thorough excavation of Petra’s hidden chambers would cost between $50-100 million. They’d need advanced technology, international teams, and years of work. Jordan’s government hasn’t allocated such funding for complete exploration yet.

Are There Any Safety Risks When Exploring Undiscovered Areas?

Yes, explorers face significant safety risks including unstable rock formations that haven’t been tested, potential cave-ins, toxic gases trapped in sealed chambers, and structural weaknesses that’ve developed over centuries without maintenance or inspection.

Which Organizations Currently Fund Research Into Petra’s Hidden Chambers?

UNESCO, Jordan’s Department of Antiquities, and the Jordanian government primarily fund Petra’s research. International universities like Brown University and Switzerland’s University of Basel also contribute funding. National Geographic Society’s supported various archaeological projects there recently.